A Journey to Become an Assistant Professor

The 2025–2026 academic job market is officially underway! I thought this would be a great moment to share my journey through the faculty job search. My hope is that my experience might offer clarity and practical insights for anyone applying or preparing to enter the market. Everything I share comes from my personal experience, including 6 Zoom interviews and 6 on-site interviews. Because I applied primarily to research-intensive (R1) universities, most of the information will be particularly relevant for those institutions.

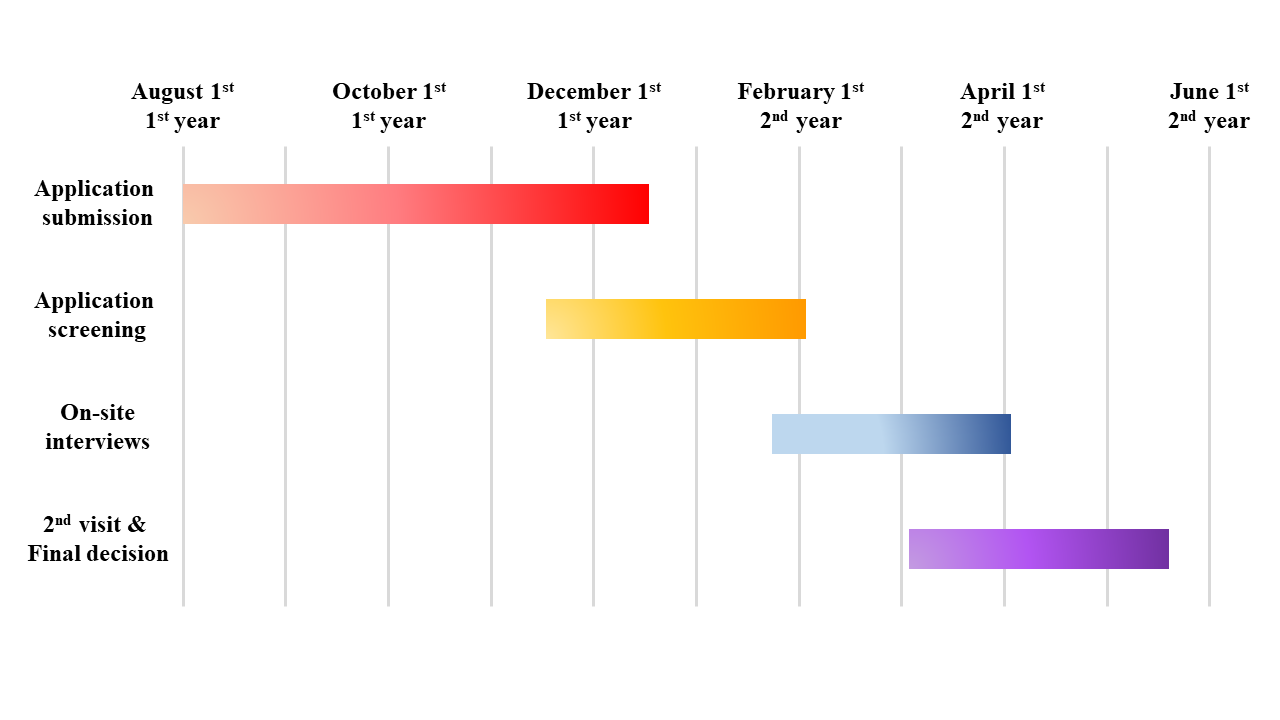

A Typical Timeline: Application to Selection:

In my experience, the academic job cycle typically starts from late August of one year till May of the next. While each institution moves at its own pace, the process generally follows several major phases:

Job announcement and application submission (August–early December, Year 1). While there are often out-of-cycle postings, the majority of R1 positions are advertised in this timeframe.

Application screening (November, Year 1–January, Year 2): After the application deadline, committees begin screening submissions and develop a preliminary short list. Some institutions invite candidates directly to on-site interviews, but these days, most conduct a Zoom interview as a first step. These virtual interviews serve as a critical initial round of screening.

On-site interviews (Late January–March, Year 2): Usually 3–6 candidates move forward to this stage, which can vary widely by institution. Some host all candidates together in a symposium-style format, while others prefer individual visits, often one person per week.

Final decision and second visit (March–April, Year 2): After on-site interviews conclude, the search committee identifies their top candidates. Offers are usually made sequentially in order of preference. The top candidate is typically invited for a second on-site visit that is focused on recruitment.

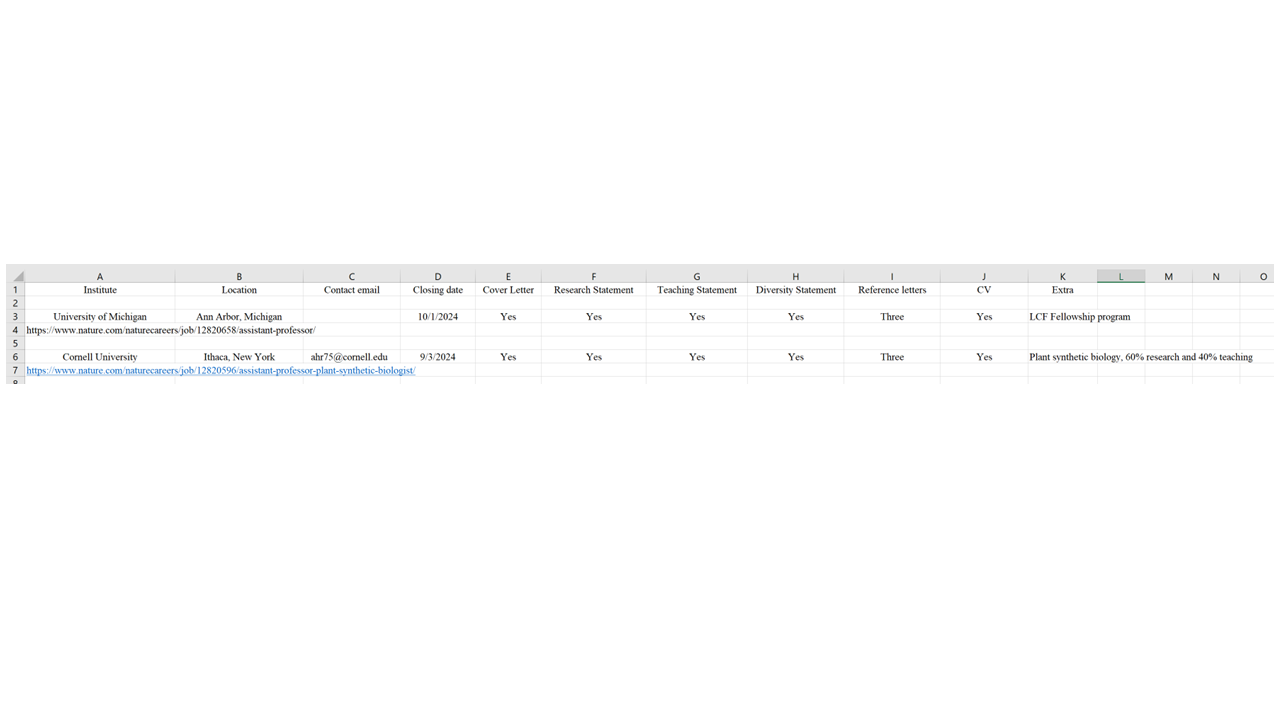

Organizing Information for the Job Search: Staying organized is essential, especially if you are juggling multiple applications and deadlines. There are several ways to identify open faculty positions:

Online Platforms: Websites like Science Careers, Nature Careers, and Google Careers regularly post faculty openings across disciplines. These are publicly accessible and easy to filter by field and location.

Word of Mouth: Search committees often share job advertisements through their personal networks. Mentors, advisors, collaborators, and colleagues can be great sources of information.

Direct Invitations: In some cases, search committees may reach out to you directly if they feel your work aligns well with their department’s priorities. These invitations typically come from people already familiar with your research.

Community Channels: Slack groups (https://futurepislack.wordpress.com/) and other job-application working groups are also valuable. Many of these communities share postings quickly and keep each other updated throughout the job cycle.

Tip #1: Attend conferences and workshops during the summer leading into the job market cycle, especially if you have opportunities to give oral presentations. These events may help to showcase your work and inform the community that you are entering the job market.

Tip #2: Create a job-tracking spreadsheet, including deadlines, required materials, and status updates. This simple organization is extremely helpful as you start managing multiple applications.

Application Package Assembly: Each institution has its own requirements for application materials, so it is essential to ensure that your package matches their instructions exactly. Still, many core documents are similar across applications, and you can prepare templates in advance and adapt them as needed.

1.Curriculum Vitae (CV)- Your CV is one of the most important documents in your application.

There are many excellent guides available online, but in my own opinion, your CV should include the following sections:

(1) Contact Information, (2) Education, (3) Research Experience, (4) Publications, (5) Awards and Grants, (6) Presentations. (7) Teaching Experience, (8) Service and Outreach Activities

2. Cover Letter- The cover letter (1–1.5 pages) is your first major opportunity to convince search committees that you are an excellent fit for their position and are thrilled to join their department. In my opinion, a cover letter typically should include:

(1) A brief introduction: Who you are, what position you are applying for, and a concise summary of your research area.

(2) Your strengths: Highlight your major accomplishments in research, teaching, mentoring, and service that demonstrate readiness for an independent faculty role.

(3) Fit with the department: Describe how your expertise complements existing strengths in the department and how you envision contributing to their community.

(4) References and closing: Include reference information and end with an enthusiastic closing paragraph.

3. Research Statement- The research statement (typically 3-4 pages) should clearly describe: (1) Your central scientific question or overarching research theme (2) Your prior research achievements that demonstrate your ability to tackle this question/theme (3) Your future research program, ideally organized as 2–3 coherent projects. I found it helpful to frame my future projects like mini grant proposals.

4. Reference Letters- Most applications require 3–5 reference letters. It is important to coordinate early with your referees to confirm they are willing and available (very important!) to support your applications in the necessary timeframe. It is best to let them know: (1) The approximate number of institutions you plan to apply to (2) The general timelines and important deadlines. A lot of universities initially request only contact information and will reach out to references if you make their shortlist. Others require full letters at the time of application. Make sure to notify your referees at least one week before deadlines and keep a careful record of letter submissions. The online application system generally keeps a record of the status of all application materials, including the submission of recommendation letters.

In addition to the core documents, several other materials are frequently required:

1. Teaching and Mentoring Statement: A 1–3 pages document that outlines (1) Your teaching and mentoring philosophy (2) Relevant teaching or mentoring experiences (3) Your vision for teaching and mentoring as a future PI in the department.

If you have teaching evaluations or evidence of mentorship outcomes, these can sometimes be included as supplemental materials.

2. Service (or Diversity) Statement: Many universities previously requested a diversity statement, but the trend is shifting to a service statement. A 1–2 pages statement should address: (1) What you understand service to be and why you think it is important (2) What you have done to serve your scientific and local communities (3) What you plan to contribute as a future faculty member.

3. Representative Publications: Some applications ask for 3–5 representative papers that best illustrate your research contributions. Choose publications that are impactful and most relevant to the position.

Tip #3: I prepared a 3-page research statement as my default template and adjusted spacing and formatting when 2- or 4-page versions were requested. This saved significant time, although additional content editing was still necessary.

Tip #4: In general, shorter documents are more effective. Committees may review hundreds of applications, so clarity and brevity are valuable. I kept both my teaching and service statements to one page whenever possible.

Tip #5: Starting early is always better. Preparing the application materials often would take more time than we estimated. Also, Submit your materials at least one day before the deadline. University recruitment portals occasionally experience glitches, and submitting early ensures your package is received. For all the applications I submitted, all the systems send an automated confirmation email.

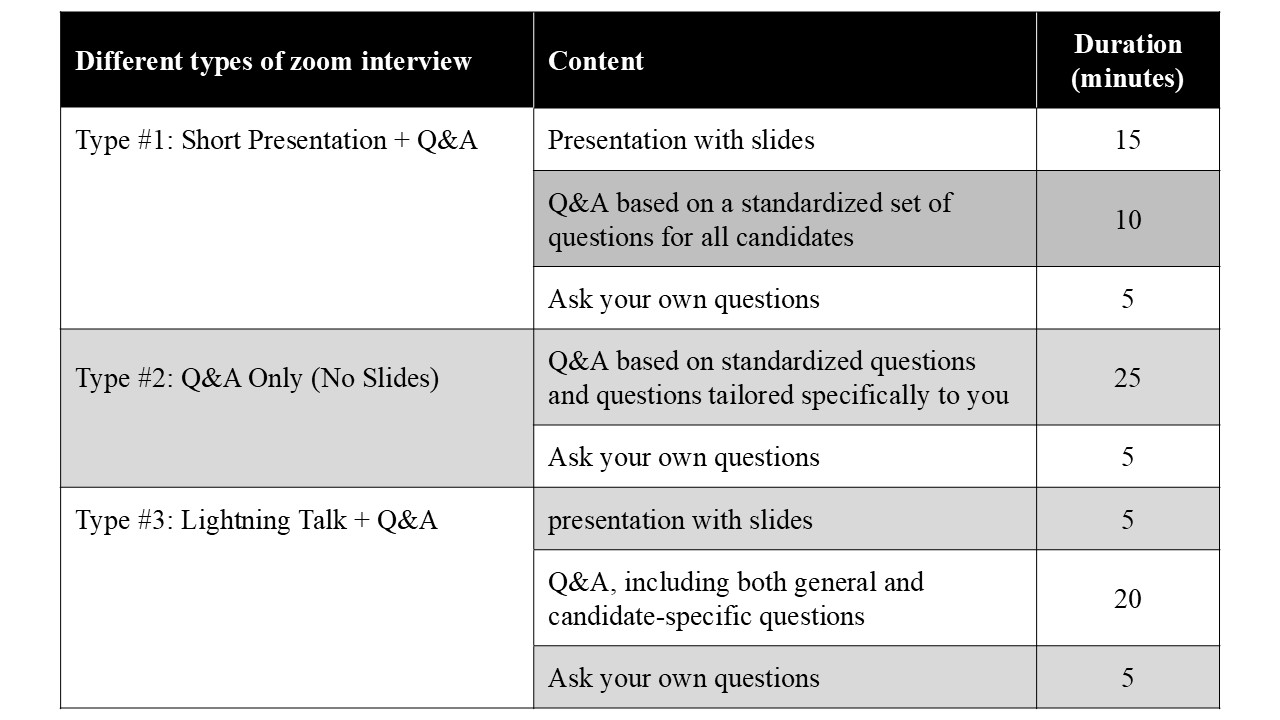

Zoom Interview: Zoom interviews vary widely depending on search committee preferences, but most follow a recognizable structure. Here are a few formats I personally encountered:

Regardless of format, Zoom interviews move quickly and are designed to assess clarity of communication, fit with the department, and enthusiasm for the position.

Common Question List:

Briefly introduce yourself

What are your research accomplishment?

What are your future research plans?

Tell us one key/central question specific to your field.

How do you fit with our department/why do you want to join us?

What is the biggest conflict/trouble you have ever been involved in at work?

Do you have any questions for us?

Tip #6: Practicing your presentation is key! It helps if you practice in front of a mirror or with a colleague or family member face to face, or even record yourself (e.g., via Zoom's record function)

Tip #7: Don’t underestimate the value of your questions. The final few minutes are an important opportunity to show you’ve done your homework and express your enthusiasm for the position.

On-site interview: I encountered two major formats during on-site interviews: Symposium-style and Individual (personal) interviews. In the symposium-style format, you visit campus with other candidates and can attend each other’s seminars. In the individual format, you are the sole interviewee during your visit. Personally, I preferred the individual format because it allowed for a more focused schedule.

Regardless of format, on-site interviews typically include the following components:

One-on-one Faculty Meetings: You meet individually with many faculty members, including future colleagues, the department chair, and sometimes the dean.

Research Seminar: A 40–50-minute formal seminar followed by 10–20 minutes of Q&A. This is your opportunity to showcase your research and scientific vision.

Chalk Talk: A 1–1.5-hour session, without slides, dedicated to your future research program and sometimes also your teaching/mentoring plans. The session is very interactive, and the audience may interrupt at any point with questions.

Meals: Lunch is often with trainees (graduate students and postdocs). Dinner is commonly with faculty members. Both offer important opportunities to learn about the department’s atmosphere and culture.

Core Facility Tours: You may visit imaging centers, genomics facilities, greenhouses, or other campus resources relevant to your work.

Tip #8: Before your visit, you should receive a list of faculty you’ll meet. Review their recent publications and websites so you can hold engaging conversations.

Tip #9: For the chalk talk, prepare multiple versions (2-, 5-, 10-, and 15-minute outlines for each project) so you can adapt depending on time and interruptions. It is normal not to finish the full chalk talk. The goal is to communicate your ideas clearly while engaging with their questions.

2nd visit: Congratulations! Reaching this stage usually means you have received an offer for the position. At this point, the department is now focused on recruiting you. The visit is designed to help everyone confirm that this is a good match.

A second visit typically includes:

Individual Meetings with Faculty: These conversations help you and your future colleagues clarify expectations and potential collaborations.

Meetings with Core Facility Staff: You’ll learn how the institution’s technical platforms operate and explore in detail how they could serve your research needs.

Meals and Informal Interactions: These more relaxing conversations with faculty members allow you to get a better feeling for the collegial environment.

Local Living & Community Exploration: This may include a guided tour of the local area, often with a real estate agent, to help you understand housing options, commute patterns, schools, and community life.

Negotiation: Negotiations typically occur between you and the department chair or the college dean both in person and through emails. In most cases, you will be asked to submit a start-up wish list first. The department will then respond with what can be provided directly and what may require alternative solutions.

For the negotiation, think carefully about your future life, both in the department and in the local community. Consider the following:

Research Needs: What essential equipment, spaces, or services are required for your day-to-day research? Are there shared facilities that can meet some needs?

Teaching Expectations: What is the typical teaching load for this position? Course assignment. Expected class sizes. TA support. When you have to start teaching?

Mentoring & Lab Personnel: Salary expectations and funding models for postdocs and technicians. Details of the graduate program (rotations, direct admission, timelines). Guaranteed funding for graduate students (fellowships, TAs).

Personal/family financial support: Your annual salary. Availability of summer salary support. Whether spousal/partner hiring programs exist. Availability of loans for house purchases. Relocation expenses.

Timeline & Tenure Clock: Official start date. Tenure-clock policies and possibilities for extensions (e.g., parental leave). Bridge funding or early-arrival arrangements (if needed).

The key thing is to communicate your needs clearly and concretely, which I feel I did not do well in my own negotiations. For example: “If A, B, and C can be provided, I will be delighted to join your department.” Once both sides reach an agreement, you will sign the final offer letter. Congratulations again, you are officially a tenure-track Assistant Professor!

Tip #10: At this stage, it is always beneficial to reach out to others, including peers who have gone through or are currently going through the process, trusted advisors (from graduate school and postdoctoral training), or a supportive group, for negotiation templates, practical suggestions, and mental support.