Meet NAASC Member Wolfgang Busch…

An interview by Early Career Scholar NAASC member Dr. Mingyuan Zhu, now an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University, USA

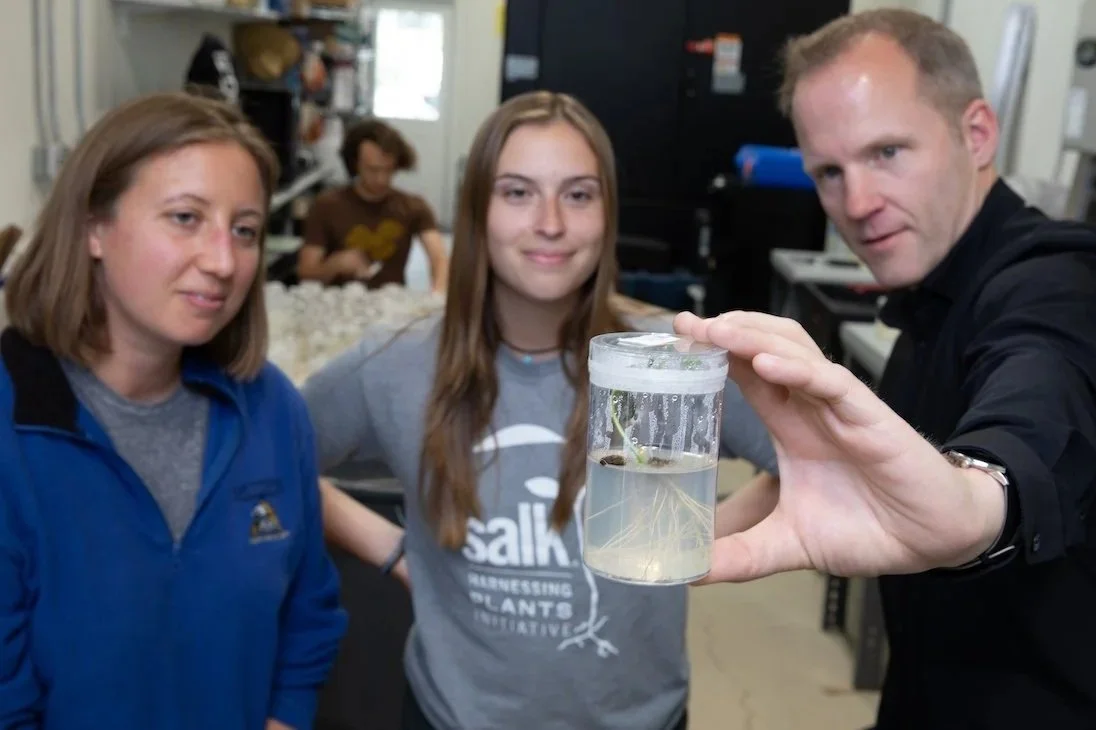

In 2017, Wolfgang came to the Salk as an Associate Professor in the Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory. He is now Professor and Director of Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory and the Executive Director of Harnessing Plant Initiative at the Salk Institute.

Wolfgang was elected to NAASC in 2024 and serves until 2029.

Briefly, when was your first encounter with Arabidopsis and what convinced you to work on Arabidopsis as your model organism? Wolfgang: I was first introduced to Arabidopsis during my undergraduate studies at the University of Tübingen in the late 1990s. At the time, Tübingen was a major hub for the emerging plant model community, and I had the opportunity to attend lectures by pioneers in the field, including Dr. Gerd Jürgens. With so many labs at Tübingen studying Arabidopsis, it naturally felt like an exciting and rapidly developing area.

Initially, however, I was more drawn to microbiology. My shift toward plant biology happened during an internship at UC San Diego in the early 2000s, where I was exposed to bioinformatics and genomics. After returning to Tübingen, I initiated projects using computational approaches to study plant responses to high-temperature stress. I started to feel the beauty of plant research. With the Arabidopsis genome already sequenced and the Salk mutant collection available, it became the perfect system for investigating how plants respond and adapt to environmental conditions in a sophisticated manner. It eventually set the foundation for my own career.

What do you think a major yet unanswered question in the plant sciences is?

Wolfgang: One major open question is how plants coordinate their growth and development to become the highly integrated and robust systems that they are. Specifically, we still do not fully understand whether plants possess an internal representation or overarching organizational framework to guide organ patterning and developmental decisions. It could be analogous in some ways to the neuron-based systems found in animals.

If you were to start your professional journey today (imagine yourself as a brand-new graduate student), which subfield of plant sciences would you now choose and why?

Wolfgang: I would still choose a field with a strong emphasis on genetics. Despite the tremendous progress made, we are still far from fully understanding the complexity of genetic functions and regulatory networks in plants. Genetics remains important and incredibly powerful to uncover how plants grow, adapt, and respond to their environment.

All scientists experience some ups and downs in their careers. Do you recall any moments in your professional life where you doubted your ability to keep going?

Wolfgang: I have experienced many challenging moments, from experiments that failed, to grant applications that were not funded, to review comments that felt unfair. These setbacks are inevitable parts of doing science.

However, for me, these discouragements never last long. With time, things do get easier, especially when you learn to step back, take a breath, refocus on science itself.

Many plant scientists today struggle with getting their project ideas funded. Do you have any advice on getting funding for Arabidopsis research, especially in today’s highly competitive climate?

Wolfgang: It varies from country to country, but a few principles apply broadly. First, stay open to diverse opportunities and think creatively about where your research interests fit. For example, agencies such as the NIH can also support plant research when the questions align with their mission. It is crucial to clearly state how fundamental discoveries in Arabidopsis connect to the broader goals and priorities of the funding agency.

Here’s a relevant perspective article that I coauthored with several NAASC members and others in the community: Friesner et al., Plant Cell (2025).

For international collaborative grants, the environment can be more challenging, but collaboration remains powerful. If you want to go far, go together! Building strong partnerships can open doors to additional funding avenues.

What do you think are the top 1-3 barriers for the next generation making a career in plant biology, and do you have any thoughts on how to overcome them?

Wolfgang: One major challenge is making plant research more compelling and clearly communicating its significance to the next generation. Much of this comes down to storytelling capacity.

A second barrier is the availability of stable and sufficient funding to support young scientists. Ensuring that early-career researchers have the resources they need is essential.

When you hire into your own lab, what are you looking for in a prospective employee?

Wolfgang: I look for a strong track record of accomplishments. It shows the great passion for science and the drive to complete projects. I value candidates who deeply understand their own research and don’t remain at the surface.

Another essential factor is fit within the lab environment. I am very proud of the supportive and collaborative community in my current group.

Wolfgang’s Brief Bio…

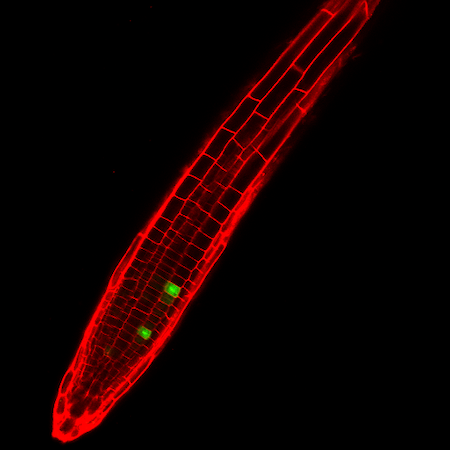

Dr. Wolfgang Busch did his undergraduate studies in Biology at the University of Tübingen, Germany. During this time, he also spent 8 months at UC San Diego where he received training on computational biology and conducted research on transporter proteins. During his PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen, he identified novel key regulatory genes and modules for plant stem cell control via a systems biology approach integrating transcriptome- and genome-scale transcription factor-DNA binding data. Wolfgang received his PhD in 2009 from the University of Tübingen. During his postdoctoral training at Duke University, he contributed to the discovery of spatiotemporally defined regulatory modules that control proliferation of stem cells and differentiation in the root and used high-throughput confocal microscopy to capture dynamic features of gene expression.

In 2011, he joined the Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology in Vienna as a group leader. During this time, he established his research program in root systems genetics and focuses on understanding which genes, genetic networks, and molecular processes determine root growth and its responses to the environment. In 2017, he came to the Salk as an Associate Professor in the Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory. He is now Professor and Director of Plant Molecular and Cellular Biology Laboratory and the Executive Director of Harnessing Plant Initiative at the Salk Institute. (Adapted from the Busch Lab website)